Introduction

Michigan forests have always been important to the quality of life for Michigan citizens, but our demands on forests continue to grow and to change. To maintain our quality of life, the way we manage our forests will also need to change. The Michigan Society of American Foresters (MSAF) offers this publication of forest management guidelines to help readers better understand forest management in Michigan.

These forest management guidelines recognize the renewable nature of forests and the influence of forest management practices on the many uses of the forests including timber, water, recreation, wildlife, visual quality, and energy. Because of the diversity of forest conditions, values, and ownerships, no set of management guidelines can cover all situations. Forest owner and professional judgment must combine scientific knowledge and local conditions to determine management practices for a particular property. These guidelines can help.

The goal of these guidelines is to provide for conservation and stewardship of all forest lands in Michigan. The MSAF challenges landowners, forest managers, forest industries, and timber harvesting contractors to follow these guidelines. They provide a common-sense approach to better manage the forest lands of the state. At the end of this document are listed a number of organizations that can assist forest owners with their management needs.

Management Guidelines: Applicable to Public & Private Forest Land

These guidelines are written to apply to all forest land ownerships in Michigan. They define a set of considerations that, when taken as a whole, constitute a framework of advice, encouragement, and obligation appropriate for the time and place for which they are written.

The guidelines represent neither a minimum set of requirements that applies in all situations, nor a guarantee that, if applied, all important considerations and obligations will be met. They are not intended as a complete forest management instruction manual for foresters, landowners, or the public.

Therefore, these guidelines must be supplemented with knowledge of local conditions, a familiarity with forest ecology and management, recognition of the objectives and constraints of individual forest owners, and compliance with all applicable laws and regulations. To ensure that these factors are carefully weighed, the advice of trained, experienced, and thoughtful professional foresters and other resource managers is available and should be sought and considered.

These forest management guidelines recognize the renewable nature of forests and the influence of forest management practices on the many uses of the forests including timber, water, recreation, wildlife, visual quality, and energy. Because of the diversity of forest conditions, values, and ownerships, no set of management guidelines can cover all situations. Forest owner and professional judgment must combine scientific knowledge and local conditions to determine management practices for a particular property. These guidelines can help.

The goal of these guidelines is to provide for conservation and stewardship of all forest lands in Michigan. The MSAF challenges landowners, forest managers, forest industries, and timber harvesting contractors to follow these guidelines. They provide a common-sense approach to better manage the forest lands of the state. At the end of this document are listed a number of organizations that can assist forest owners with their management needs.

Management Guidelines: Applicable to Public & Private Forest Land

These guidelines are written to apply to all forest land ownerships in Michigan. They define a set of considerations that, when taken as a whole, constitute a framework of advice, encouragement, and obligation appropriate for the time and place for which they are written.

The guidelines represent neither a minimum set of requirements that applies in all situations, nor a guarantee that, if applied, all important considerations and obligations will be met. They are not intended as a complete forest management instruction manual for foresters, landowners, or the public.

Therefore, these guidelines must be supplemented with knowledge of local conditions, a familiarity with forest ecology and management, recognition of the objectives and constraints of individual forest owners, and compliance with all applicable laws and regulations. To ensure that these factors are carefully weighed, the advice of trained, experienced, and thoughtful professional foresters and other resource managers is available and should be sought and considered.

Characteristics of Michigan's Forests

Michigan's temperate forests teem with plant and animal life, provide outdoor recreation opportunities, protect and enhance air and water quality, and support thousands of jobs. They contribute billions of dollars to Michigan’s economy each year. Michigan forests touch our lives each day.

Forested ecosystems include living and non-living components combined into a much broader landscape diversity mix. The mix of biotic components helps define biodiversity. In the case of forests, the kinds of vegetation present determine the kinds of mammals, birds, amphibians, and other organisms which can survive. In 2007, Michigan's statewide forest inventory (USDA Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis program) identified over 100 different tree species.

The forest also contains other living components which are part of its overall health. These include lichens, mosses, dead and/or downed woody vegetation, fungi, and herbaceous plants. The relationship of these many components to one another creates different but important habitat. Examples are the edge between various forests or land uses and the presence of aquatic systems.

Forests dominate Michigan's landscape. In 2007, they covered 54% of the total land area, representing 19.7 million acres. Nearly all of these forest lands meet minimum tree growth productivity standards (20 cubic feet per acre per year) to produce commercial timber crops, qualifying as timberland. Originally intended for industrial wood production, this classification provides a good measure of the forest's potential to produce a wide array of goods and services. Timberland area has increased 10%, to 19.2 million acres, since 1980.

Forested ecosystems include living and non-living components combined into a much broader landscape diversity mix. The mix of biotic components helps define biodiversity. In the case of forests, the kinds of vegetation present determine the kinds of mammals, birds, amphibians, and other organisms which can survive. In 2007, Michigan's statewide forest inventory (USDA Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis program) identified over 100 different tree species.

The forest also contains other living components which are part of its overall health. These include lichens, mosses, dead and/or downed woody vegetation, fungi, and herbaceous plants. The relationship of these many components to one another creates different but important habitat. Examples are the edge between various forests or land uses and the presence of aquatic systems.

Forests dominate Michigan's landscape. In 2007, they covered 54% of the total land area, representing 19.7 million acres. Nearly all of these forest lands meet minimum tree growth productivity standards (20 cubic feet per acre per year) to produce commercial timber crops, qualifying as timberland. Originally intended for industrial wood production, this classification provides a good measure of the forest's potential to produce a wide array of goods and services. Timberland area has increased 10%, to 19.2 million acres, since 1980.

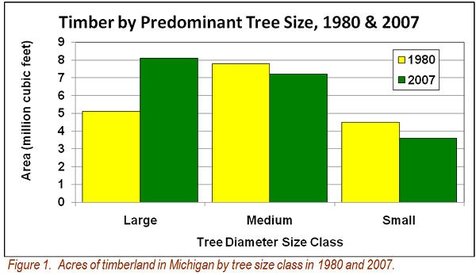

Michigan's forests continue to mature and regenerate, altering forest structure continually. One measure of this process is reflected in the statewide forest inventory. Since 1980, Michigan's forest acreage of large diameter trees (roughly, trees greater than 10 inches) increased 59%; medium diameter (5 to 10 inch trees) acreage decreased 6%; and small diameter (trees smaller than 5 inches) decreased by 19% (Figure 1). Michigan’s forests are growing in area and size. The trend towards maturity in Michigan's forests provides a variety of management opportunities, such as managing for old growth attributes, harvesting mature trees, improving structural diversity, or regenerating young forests.

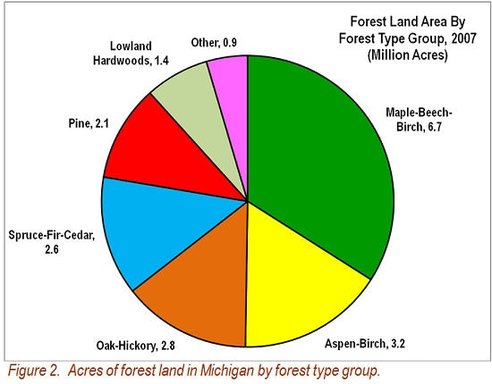

Certain tree species in the forest grow near one another due to similar soil, moisture, climate, terrain, and past history. These tree species communities are called forest types and they can be categorized into forest type groups. Hardwood forest type groups (broadleaf deciduous tree species like oak, aspen, and maple) are the most common in Michigan forests. They account for approximately 75% of the forest land. Softwood forest type groups (comprised of tree species like pine, spruce, and cedar) account for the remainder. The two largest forest type groups in Michigan are maple‑beech‑birch (commonly referred to as northern hardwoods) at 6.7 million acres and aspen-birch at 3.4 million acres (Figure 2).

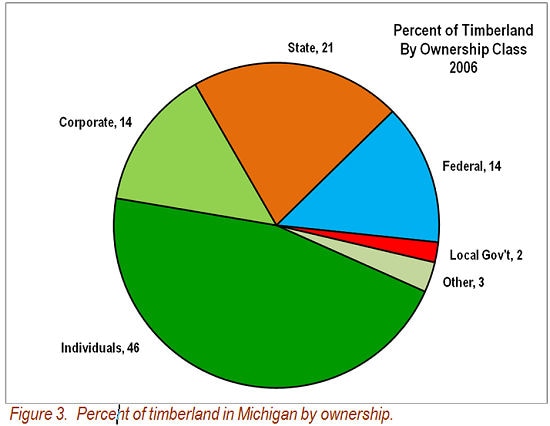

Private owners hold 63% of the state's timberland acres. They include 444,000 private forest land owners with an average ownership of 27 acres. Non‑industrial private (farmers, individuals, hunt clubs, etc.) ownership is 49% of the total (Figure 3). Corporate and forest industry ownership is 14% of the state total. These collective private holdings have a range of management objectives, including investment, recreation, and scenery. These owners generally have a strong land ethic and respond to opportunities to improve their property's values. Public ownership accounts for the remaining 38% of the total timberland base. National forests in Michigan include the Ottawa, Hiawatha, and the Huron‑Manistee, which represent 14% of the total. State-owned forest lands represent 21% of the total. A small fraction of public ownership is held by counties, municipalities, and various federal agencies. Principal ownership objectives of public lands include community stability through support for timber and recreational industries and the more naturalistic values associated with such things as environmental services and wild lands. Tribal governments, non-government conservation organizations, hunt clubs, and other private organizations account for the “other” timberland owners.

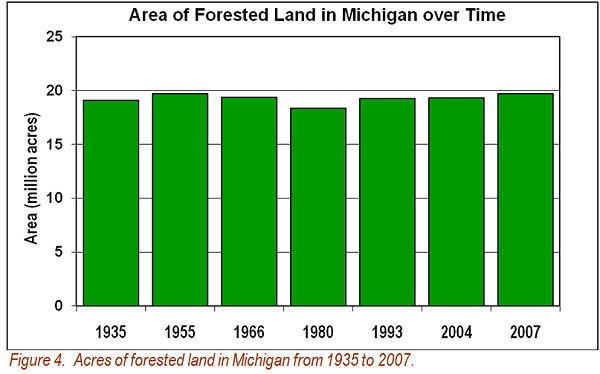

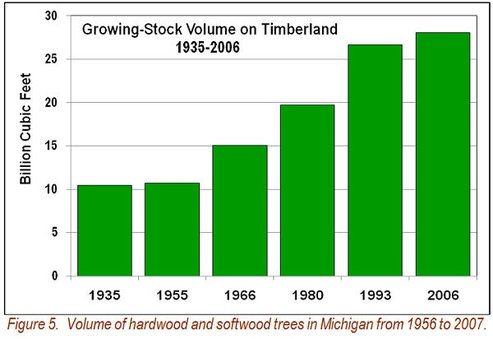

Though the total area of forest land in Michigan has changed little since the first Forest Inventory and Analysis survey was completed in 1935 (Figure 4), the volume of wood in the forest has risen (Figure 5). The 1955 survey estimated that Michigan had 10.7 billion cubic feet of growing stock (trees 5 inches in diameter and larger). By 2007, the inventory had increased to 28.3 billion cubic feet. Between 1980 and 2007, the inventory increased over 8.6 billion cubic feet, a 44% increase. Hardwoods make up over two-thirds of the growing-stock volume.

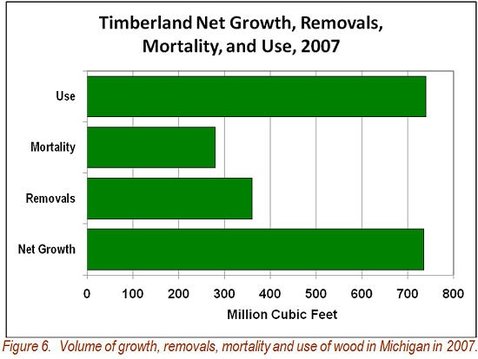

Michigan's forests are currently growing twice as much wood (736 million cubic feet) as is being removed (363 million cubic feet) from the timberland base each year (Figure 6). Net growth represents growth minus mortality. Removals of wood include both harvests and diversions from timberland. Mortality due to old age, fire, wind, insects, and disease was 277 million cubic feet. In this same period, Michiganders consumed 740 million cubic feet of wood products (paper, lumber, furniture, etc.).

Michigan's surplus growing stock (annual net growth less removals) is among the largest in the nation, but there is potential to increase growth even more. Given favorable climate and soils and using forest management in a timely manner, growth can be increased by assuring fully stocked acres. Additional increases in wood growth can occur through the use of more active forest management techniques such as thinning and planting genetically improved trees.

Contributions of Michigan’s Forests

Michigan's forests contribute to the well‑being of society by enhancing environmental quality, maintaining habitat for wildlife, providing recreational opportunities and settings, growing timber, and creating jobs to produce and manufacture wood and wood products.

Although difficult to measure, Michigan's forests provide valuable environmental benefits by improving air and water quality and enhancing natural resource conservation. Forests filter pollutants from ambient air. A well-managed, growing forest in Michigan can sequester up to a ton or more of carbon per acre from the atmosphere each year until maturity. This is an important ecosystem service that, among other things, can offset excess fossil fuel emissions of carbon dioxide. Forests protect watersheds from erosion and degradation, filter runoff and recharge ground water, and shade streams and lakes. They enhance the quality of Michigan's 36,350 miles of rivers and streams, its 11,037 inland lakes and its drinking water.

Forests help conserve many natural resources. Threatened, endangered, or animals of special concern like the bald eagle, Kirtland's warbler, moose, gray wolf, pine marten, and fisher, along with many rare plants, are found within Michigan forests, especially in wetlands. Some of our forests also serve as biological reserves to protect diverse habitats and genetic material.

Michigan forests provide habitat for wildlife, including the state's estimated 1.7 million deer, and watershed protection for its inland fishery. In 2006, 1.7 million Michigan residents fished or hunted and 2.9 million residents participated in other wildlife-watching recreation. Anglers spent $1.7 billion in Michigan in 2006, participants in hunting spent $916 million, and other wildlife watchers spent $1.6 billion.

Michigan has 7.2 million acres of state and federal forest land that can be used for outdoor recreation. State forests hold 59% and national forests hold 41% of these lands. State and federal wilderness areas total over 322,000 acres. This land base provides opportunities for camping, hiking, skiing, stream and inland lake fishing, berry and mushroom picking, trail biking, and horseback riding. Forests are the setting for many tourist-related activities. Tourists spent $8.8 billion in 2000, much of it in forest-dependent counties.

Although difficult to measure, Michigan's forests provide valuable environmental benefits by improving air and water quality and enhancing natural resource conservation. Forests filter pollutants from ambient air. A well-managed, growing forest in Michigan can sequester up to a ton or more of carbon per acre from the atmosphere each year until maturity. This is an important ecosystem service that, among other things, can offset excess fossil fuel emissions of carbon dioxide. Forests protect watersheds from erosion and degradation, filter runoff and recharge ground water, and shade streams and lakes. They enhance the quality of Michigan's 36,350 miles of rivers and streams, its 11,037 inland lakes and its drinking water.

Forests help conserve many natural resources. Threatened, endangered, or animals of special concern like the bald eagle, Kirtland's warbler, moose, gray wolf, pine marten, and fisher, along with many rare plants, are found within Michigan forests, especially in wetlands. Some of our forests also serve as biological reserves to protect diverse habitats and genetic material.

Michigan forests provide habitat for wildlife, including the state's estimated 1.7 million deer, and watershed protection for its inland fishery. In 2006, 1.7 million Michigan residents fished or hunted and 2.9 million residents participated in other wildlife-watching recreation. Anglers spent $1.7 billion in Michigan in 2006, participants in hunting spent $916 million, and other wildlife watchers spent $1.6 billion.

Michigan has 7.2 million acres of state and federal forest land that can be used for outdoor recreation. State forests hold 59% and national forests hold 41% of these lands. State and federal wilderness areas total over 322,000 acres. This land base provides opportunities for camping, hiking, skiing, stream and inland lake fishing, berry and mushroom picking, trail biking, and horseback riding. Forests are the setting for many tourist-related activities. Tourists spent $8.8 billion in 2000, much of it in forest-dependent counties.

|

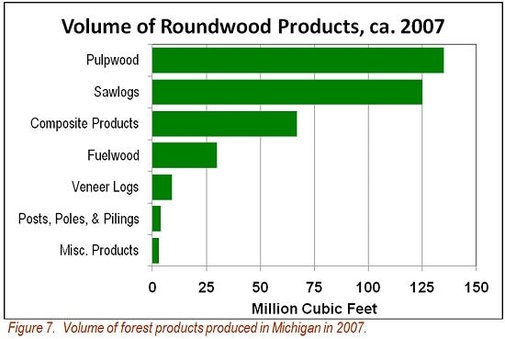

Michigan produces a vast array of forest products, from paper to Christmas trees. Industrial production of sawlogs, pulpwood, veneer logs, and other timber products totaled 373 million cubic feet in 2007 (Figure 7). Additionally, domestic fuelwood production is increasing as costs of other forms of home heating are increasing.

|

|

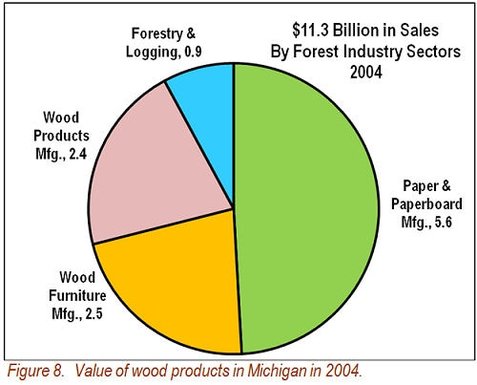

Over 1,600 firms were involved in forest products harvesting, transporting, brokering, or manufacturing in Michigan in 2004. Manufacturing accounted for about three‑quarters of these firms whose sales totaled $10.5 billion (Figure 8). These sales, in turn, generated almost $9 billion in additional sales in Michigan’s economy. Lumber and wood products, wood furniture, and pulp and paper products contributed over $3.4 billion in value added to Michigan's economy. Pulp and paper products manufacturing contributed about 42% of this total. In 2004 these industries, including logging, provided direct employment to over 46,000 people. These jobs generated 58,200 additional jobs outside the forest products industry.

|

In addition to the more traditional forest products and services, there is a renewed interest in wood-based energy and evolving roles for ecosystem services (carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, etc.). These emerging markets herald a larger role for forests in Michigan’s economy.

Ecosystem services are all of the benefits that the environment provides to society. Healthy forest ecosystems provide numerous services, including oxygen, watershed protection, timber production, energy, plant pollination, wildlife habitat, biodiversity, and scenic landscapes. Landowners that practice sustainable forest management not only create healthy and resilient forests for their own use and enjoyment, they are also performing an activity that benefits all other citizens.

Traditionally, ecosystem services have been seen as free services or “public goods” and have not had an economic value in society. However, new markets are emerging that may be able to generate incentives for people who provide these services. In the future, forest owners may be able to participate in markets and generate revenue that will help balance the costs of producing these benefits and increase the societal value of forest lands.

One example of these emerging markets is carbon trading. As trees live and grow, they absorb carbon dioxide from the air and store, or sequester, it in their wood, in the soil, and in wood products. Planting trees and managing forests in a way that encourages healthy and vigorous tree growth can help to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which will help to mitigate climate change. In the future, carbon markets may allow forest owners to receive payments for forest management activities that will sequester additional carbon from the atmosphere.

Forest land provides many rewards to the forest owner as well as services to society. Michigan’s citizens and visitors benefit greatly from the nearly 20 million forested acres in the state. Some of these benefits provide financial returns, such as those from forest products or hunting fees. Other ecosystem services are equally important but are not as easy to market and sell, such as beauty, solitude, and the joy of being a steward over a part of nature. With the possibility of new markets, forest owners may begin to see a return on investment for the ecosystem services that they have provided for free. For example in 2008, investors received approximately $400,000 for sequestering carbon on their forest land.

Ecosystem services are all of the benefits that the environment provides to society. Healthy forest ecosystems provide numerous services, including oxygen, watershed protection, timber production, energy, plant pollination, wildlife habitat, biodiversity, and scenic landscapes. Landowners that practice sustainable forest management not only create healthy and resilient forests for their own use and enjoyment, they are also performing an activity that benefits all other citizens.

Traditionally, ecosystem services have been seen as free services or “public goods” and have not had an economic value in society. However, new markets are emerging that may be able to generate incentives for people who provide these services. In the future, forest owners may be able to participate in markets and generate revenue that will help balance the costs of producing these benefits and increase the societal value of forest lands.

One example of these emerging markets is carbon trading. As trees live and grow, they absorb carbon dioxide from the air and store, or sequester, it in their wood, in the soil, and in wood products. Planting trees and managing forests in a way that encourages healthy and vigorous tree growth can help to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which will help to mitigate climate change. In the future, carbon markets may allow forest owners to receive payments for forest management activities that will sequester additional carbon from the atmosphere.

Forest land provides many rewards to the forest owner as well as services to society. Michigan’s citizens and visitors benefit greatly from the nearly 20 million forested acres in the state. Some of these benefits provide financial returns, such as those from forest products or hunting fees. Other ecosystem services are equally important but are not as easy to market and sell, such as beauty, solitude, and the joy of being a steward over a part of nature. With the possibility of new markets, forest owners may begin to see a return on investment for the ecosystem services that they have provided for free. For example in 2008, investors received approximately $400,000 for sequestering carbon on their forest land.

The Importance of a Forest Management Plan

Though forests can provide clean water, fuelwood, recreation, timber, wildlife and scenic value in numerous combinations, any action taken at one time may affect available choices for years to come. Forest planning can integrate and optimize management of all these forest attributes.

Forest planning is the process of comparing the forest owner’s ideas with the current condition of the woodlot and the inherent capabilities of the forest to provide goods and services on a sustainable basis. This comparison will consider any obligations or constraints pertaining to the forest owner and the property. This is the first step in active forest management, which may include timber harvesting, tree and shrub planting for timber production or wildlife habitat, or even the creation of forest openings to enhance diversity.

All forest owners have a plan, even if it is simply how they imagine their woodlot in the future. The advantage of a formal written plan is that it can more easily address complex considerations and resolve possible inconsistencies and conflicts between desired outcomes. A written plan is an excellent way to convey one’s vision of the property to the next generation. It also serves as a helpful reminder of our vision of the future. Management plans are useful when one participates in conservation programs, Tree Farm or other sustainable management schemes, Michigan’s property tax relief programs, or carbon trading.

Forest planning is the process of comparing the forest owner’s ideas with the current condition of the woodlot and the inherent capabilities of the forest to provide goods and services on a sustainable basis. This comparison will consider any obligations or constraints pertaining to the forest owner and the property. This is the first step in active forest management, which may include timber harvesting, tree and shrub planting for timber production or wildlife habitat, or even the creation of forest openings to enhance diversity.

All forest owners have a plan, even if it is simply how they imagine their woodlot in the future. The advantage of a formal written plan is that it can more easily address complex considerations and resolve possible inconsistencies and conflicts between desired outcomes. A written plan is an excellent way to convey one’s vision of the property to the next generation. It also serves as a helpful reminder of our vision of the future. Management plans are useful when one participates in conservation programs, Tree Farm or other sustainable management schemes, Michigan’s property tax relief programs, or carbon trading.

|

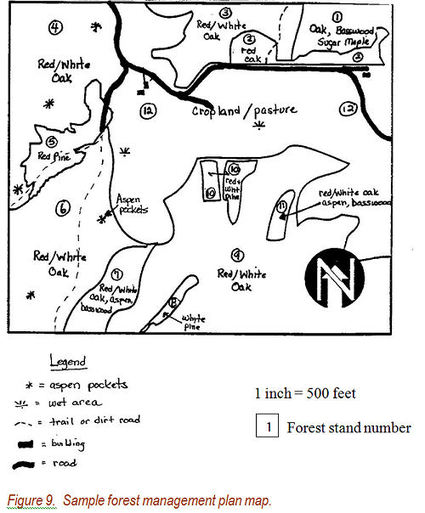

A written management plan is the blueprint of a woodlot. It begins with a statement of specific goals and objectives. Goals tend to be long-term and describe the desired future condition of the woodlot. Objectives are actions taken to achieve the goals. These are followed by a description of the woodlot and how it fits into the surrounding ecological landscape. The narrative may include physical features such as soil properties, wetlands, and topographic and hydrologic features. It details the presence of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants and wildlife, including rare and threatened species that are found or may be found there. A variety of data sources are available, including site-specific field work on a particular property. A useful map of the woodlot (Figure 9) shows the physical features of the property including the vegetative cover types (stands), roads, buildings, topographic features, and surface water. Additional maps may be added to show soils types and the locations of proposed treatments. Finally, sustainable forest management alternatives are presented that promote the forest owner’s goals.

|

Forests are dynamic and management plans must be adaptable to changing forest and market conditions. For this reason, all forest plans need to be monitored, evaluated, and periodically updated to ensure forest conditions have not changed and that the plans are still relevant.

Forest owners should consider the advice and assistance of professional foresters and other resource professionals when developing a forest plan. The scope, detail, timetable, cost, and funding of the forest plan should be agreed upon prior to its preparation. Forest owners should also consider the amount of time and financial resources required to implement provisions laid out in the plan.

Forest owners should consider the advice and assistance of professional foresters and other resource professionals when developing a forest plan. The scope, detail, timetable, cost, and funding of the forest plan should be agreed upon prior to its preparation. Forest owners should also consider the amount of time and financial resources required to implement provisions laid out in the plan.

Basic Elements of a Sound Forest Plan

- Management plans begin with a clear statement of the landowner’s objectives, both general and specific, for the short and long run.

- Maps depict the physical attributes of the property, including vegetative cover types (stands), streams, roads, wetlands and other important characteristics. Additional maps that show soil types or treatment areas may be helpful.

- A narrative description assesses the current condition of the property and its physical and biological capability to provide desired goods and services.

- An intended course of action outlines alternatives that promote sustainable forest management. This may include plans for planting, thinning and harvesting. Regular monitoring of forest resources will help keep the plan updated and relevant.

Michigan Forest Types and Their Ecology

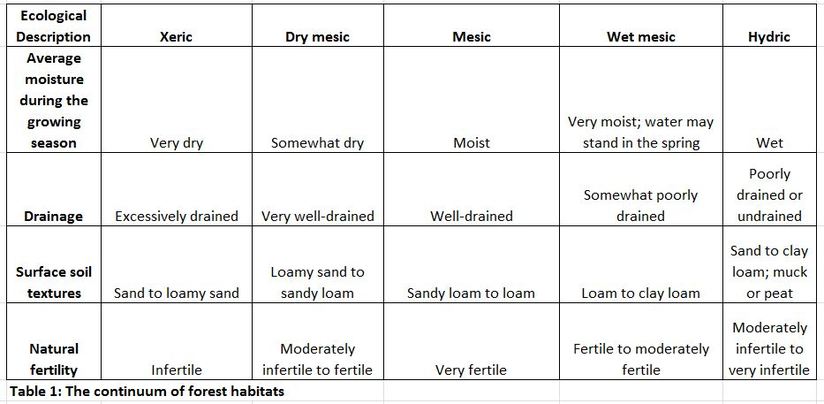

Though forests once covered about 95% of Michigan, today about half the state is forested [see Dickmann and Leefers (2003), The Forests of Michigan, for a thorough discussion of the state’s forest history]. But this forest cover varies by region: 21% of the southern Lower Peninsula is occupied by patchy woods and wetland corridors, whereas 65% of the northern Lower Peninsula and 84% of the Upper Peninsula are covered by large forested tracts. Within each region the combined effects of glacial landforms, climate, soil, and recent history have produced a variety of forest habitats (Table 1). On these unique habitats grow different forest types [see the field guide by Dickmann (2004), Michigan Forest Communities, for a complete description of Michigan forest types].

A forest type is a broadly defined ecosystem—a varied and complex community of plants, animals, and other organisms living together in a common habitat. Forest types are defined principally by their characteristic tree species. This practice does not imply that the organisms associated with these trees are somehow less important ecologically. Trees are large and structurally dominant, and they may have monetary value or aesthetic appeal; thus we focus on them. Michigan’s forests are very diverse, largely because of the extremely variable climate produced by the surrounding Great Lakes and the great south to north and east to west geography. Ten coniferous tree species and 52 hardwood or broadleaf deciduous tree species that reach commercial size are native to the state. Another 30 or so native species are considered small trees or large shrubs. A number of these large and small trees reach the northern extent of their range in the southern part of the state. But because of their unique, gene-based adaptations, these native tree species do not all grow together in the same habitat or the same geographic area of the state. Rather, in a given geographic region certain trees congregate together in a particular habitat to form a distinctive forest type.

A forest owner may learn that there are a number of different forest classification systems. For these guidelines, the forest type descriptions are grouped under three broad classes: Wetland Forest Types, Upland Forest Types and Open Canopy Forests. Forest plantations are also described.

A forest owner may learn that there are a number of different forest classification systems. For these guidelines, the forest type descriptions are grouped under three broad classes: Wetland Forest Types, Upland Forest Types and Open Canopy Forests. Forest plantations are also described.

Habitat Type Descriptions

Wetland Forest Types

The glacial landforms of Michigan, combined with normally abundant rainfall, have produced an abundance of wet (hydric) habitats, and many of these habitats are forested. Wetlands are protected under Section 404 of the Federal Clean Water Act of 1972 and Part 303 of the Michigan Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act of 1994 (P.A. 451). These acts regulate the discharge of pollutants into wetlands, the building of dams and levees, infrastructure development, and the draining of wetlands for farming, forestry, or other purposes. While nearly all forest management is guided by “best management practices” (BMPs), which are designed to protect water and soil resources, these BMPs particularly impact management of wetland forests.

The glacial landforms of Michigan, combined with normally abundant rainfall, have produced an abundance of wet (hydric) habitats, and many of these habitats are forested. Wetlands are protected under Section 404 of the Federal Clean Water Act of 1972 and Part 303 of the Michigan Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act of 1994 (P.A. 451). These acts regulate the discharge of pollutants into wetlands, the building of dams and levees, infrastructure development, and the draining of wetlands for farming, forestry, or other purposes. While nearly all forest management is guided by “best management practices” (BMPs), which are designed to protect water and soil resources, these BMPs particularly impact management of wetland forests.

- Southern Deciduous Swamps & Floodplain Forests

- Northern Hardwood Conifer Swamps

- Northern Cedar Swamps

- Northern Conifer Bogs and Muskegs

Upland Forest Types

The extensive uplands of Michigan are of glacial origin. They include hilly ice-contact features—moraines, kames, eskers, drumlins, and crevasse fillings—as well as flat or gently undulating till plains, outwash plains, and well-drained former lakebeds. Near the shore of Lake Michigan and in some inland areas, wind-shaped sand dunes also occur. In the highlands of the western Upper Peninsula, ancient bedrock forms prominent, mountainous ridges. Upland habitats are extremely diverse, with local differences in climate and history adding their influence to habitat variation.

The extensive uplands of Michigan are of glacial origin. They include hilly ice-contact features—moraines, kames, eskers, drumlins, and crevasse fillings—as well as flat or gently undulating till plains, outwash plains, and well-drained former lakebeds. Near the shore of Lake Michigan and in some inland areas, wind-shaped sand dunes also occur. In the highlands of the western Upper Peninsula, ancient bedrock forms prominent, mountainous ridges. Upland habitats are extremely diverse, with local differences in climate and history adding their influence to habitat variation.

- Southern Maple Beech Forests

- Southern Oak-Mixed Hardwood Forests

- Northern Maple-Mixed Hardwood Forests

- Northern Hemlock Forests

- Northern Oak Forests

- Northern Pine Forests

- Boreal Spruce-Fir Forests

- Aspen-Paper Birch Forests

- Plantations

Open Canopy Forest Types

Although not considered commercial forest types, small areas of open forests consisting of scattered or clumped trees—known as savannas or barrens—also occur in Michigan. They represent a transition between closed forests and prairies and are maintained by frequent disturbances, usually fire or grazing. Although they occupied more than 2 million acres in the state in the early 1800s, savannas are the rarest forest types in Michigan today.

Although not considered commercial forest types, small areas of open forests consisting of scattered or clumped trees—known as savannas or barrens—also occur in Michigan. They represent a transition between closed forests and prairies and are maintained by frequent disturbances, usually fire or grazing. Although they occupied more than 2 million acres in the state in the early 1800s, savannas are the rarest forest types in Michigan today.

- Southern lakeplain oak-hardwood openings

- Southern oak barrens

- Northern pine and oak barrens

- Great Lakes barrens

- Alvar savannas

- Pine stump plains

Management

Silvicultural Systems

Silviculture is the art and science of tending and regenerating forest vegetation. A silvicultural system is a program of treatments that are prescribed to meet the forest owner's objectives through the life of a forest. The premise underlying any silvicultural system is long‑range sustainability, both of the forest itself and the production of goods and services from it. The silvicultural prescriptions that are part of any system may include harvesting or other treatments to promote tree growth and quality, alter species composition, reduce competition, create a certain stand structure or habitat, or regenerate a new stand, and they are specific to a particular stand of trees. Prescriptions may also recommend conversion of an existing stand to a different timber or vegetation type, or they may recommend that no treatments be made.

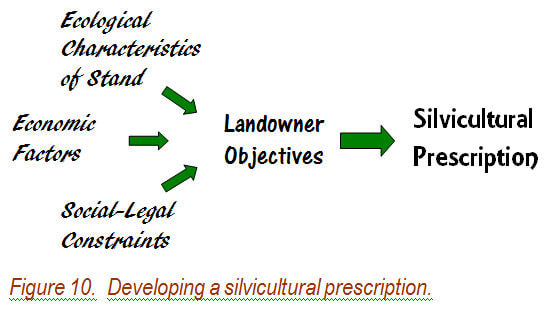

The starting point for developing silvicultural prescriptions is the forest owner objectives, which can include timber sales, wildlife habitat, visual quality or recreational considerations, high biodiversity, protection of water, minimizing pest or disease damage, or production of forest commodities like fruits, nuts, greenery, or mushrooms. A professional forester can help refine these objectives by taking into account the ecological characteristics of the stand and the site, any social or legal constraints that may exist (e.g., Best Management Practices for water quality protection or pesticide use regulations), and monetary factors, such as the need to generate income or budgetary limitations (Figure 10). Although prescriptions are developed on a stand-by-stand basis, a forest owner also must develop an understanding of how the stands in their ownership interact and how they relate to the surrounding landscape and other ownerships.

Silviculture is the art and science of tending and regenerating forest vegetation. A silvicultural system is a program of treatments that are prescribed to meet the forest owner's objectives through the life of a forest. The premise underlying any silvicultural system is long‑range sustainability, both of the forest itself and the production of goods and services from it. The silvicultural prescriptions that are part of any system may include harvesting or other treatments to promote tree growth and quality, alter species composition, reduce competition, create a certain stand structure or habitat, or regenerate a new stand, and they are specific to a particular stand of trees. Prescriptions may also recommend conversion of an existing stand to a different timber or vegetation type, or they may recommend that no treatments be made.

The starting point for developing silvicultural prescriptions is the forest owner objectives, which can include timber sales, wildlife habitat, visual quality or recreational considerations, high biodiversity, protection of water, minimizing pest or disease damage, or production of forest commodities like fruits, nuts, greenery, or mushrooms. A professional forester can help refine these objectives by taking into account the ecological characteristics of the stand and the site, any social or legal constraints that may exist (e.g., Best Management Practices for water quality protection or pesticide use regulations), and monetary factors, such as the need to generate income or budgetary limitations (Figure 10). Although prescriptions are developed on a stand-by-stand basis, a forest owner also must develop an understanding of how the stands in their ownership interact and how they relate to the surrounding landscape and other ownerships.

Once the objectives are set, the forester can work with the forest owner to implement them. If a timber harvest is planned, it is important to understand the roles of the forester and the logger. The forester is responsible for designing a forest plan, selecting the silvicultural system, planning for regeneration, determining the need for tending treatments, and arranging for the timber sale. The logger, on the other hand, is the person who does the harvesting of the trees in accord with the prescriptions developed by the forester and the forest owner.

Not all forests are managed. Not all timber harvests occur within the guidance a forest management plan. Timber harvest used to carry-out the objectives of a professionally guided plan promotes forest sustainability and increases the many values a forest owner might expect from their property. Decisions, or lack of them, have long-term impacts both ecologically and financially. Forest owners are encouraged to enlist the expertise of professional foresters when making decisions about their forests.

There are two basic silvicultural systems used in Michigan for management and regeneration of forest stands—even‑aged and uneven‑aged (also called all-aged). Under the even‑aged system, stands consist of overstory trees of the same, or nearly the same, age. The uneven‑aged system, by contrast, is applied in stands that contain trees of three or more different age classes. The choice depends on the ecology of the stand, its current structure, and the forest owner's objectives. In some cases these systems require little silvicultural input and then nature, so to speak, does all the work. In other cases more intensive or specialized techniques may be necessary to regenerate commercially or ecologically valuable species such as yellow birch, hemlock, jack pine, white cedar, and oak or to create and sustain ecologically diverse communities. These techniques may include site preparation to reduce competition and prepare a mineral soil seedbed, prescribed fire, application of herbicides, and seeding or planting.

Not all forests are managed. Not all timber harvests occur within the guidance a forest management plan. Timber harvest used to carry-out the objectives of a professionally guided plan promotes forest sustainability and increases the many values a forest owner might expect from their property. Decisions, or lack of them, have long-term impacts both ecologically and financially. Forest owners are encouraged to enlist the expertise of professional foresters when making decisions about their forests.

There are two basic silvicultural systems used in Michigan for management and regeneration of forest stands—even‑aged and uneven‑aged (also called all-aged). Under the even‑aged system, stands consist of overstory trees of the same, or nearly the same, age. The uneven‑aged system, by contrast, is applied in stands that contain trees of three or more different age classes. The choice depends on the ecology of the stand, its current structure, and the forest owner's objectives. In some cases these systems require little silvicultural input and then nature, so to speak, does all the work. In other cases more intensive or specialized techniques may be necessary to regenerate commercially or ecologically valuable species such as yellow birch, hemlock, jack pine, white cedar, and oak or to create and sustain ecologically diverse communities. These techniques may include site preparation to reduce competition and prepare a mineral soil seedbed, prescribed fire, application of herbicides, and seeding or planting.

Even-Aged Systems

The even‑aged system comprises three regeneration methods that represent a continuum of residual stand structures:

Clearcutting is the most common even‑aged regeneration method; it is most-often used to manage sun‑loving, shade intolerant species, although under the right circumstances it will successfully regenerate almost any type of forest community. In this method, an entire commercially mature stand is removed in one harvest. Aspen, because of its inherent ability to sprout from the roots of harvested trees, is the classic example of a species that regenerates well by clearcutting (Figure 11). Often small patches or a few scattered trees are left on the site for reasons of visual quality, wildlife habitat, mast (animal food) production, or biodiversity. Many applications of this method are enhanced by site preparation and planting or seeding. In some cases, advance regeneration of shade‑tolerant species (e.g., sugar maple, balsam fir, and white pine) may have become established under the trees that are harvested, presenting some options in determining the composition of the new stand.

The even‑aged system comprises three regeneration methods that represent a continuum of residual stand structures:

- Clearcutting

- Seed tree

- Shelterwood

Clearcutting is the most common even‑aged regeneration method; it is most-often used to manage sun‑loving, shade intolerant species, although under the right circumstances it will successfully regenerate almost any type of forest community. In this method, an entire commercially mature stand is removed in one harvest. Aspen, because of its inherent ability to sprout from the roots of harvested trees, is the classic example of a species that regenerates well by clearcutting (Figure 11). Often small patches or a few scattered trees are left on the site for reasons of visual quality, wildlife habitat, mast (animal food) production, or biodiversity. Many applications of this method are enhanced by site preparation and planting or seeding. In some cases, advance regeneration of shade‑tolerant species (e.g., sugar maple, balsam fir, and white pine) may have become established under the trees that are harvested, presenting some options in determining the composition of the new stand.

Figure 11. Aspen Regeneration

Seedtree and shelterwood are also called retention systems because some trees are left behind following a harvest of mature timber. In the seed tree method, nearly all of a commercially mature stand is removed in one cutting, except for a small number of trees that are left to provide seed for regenerating a new stand (Figure 12) and, sometimes, for other purposes as well. Seed trees may be scattered, in small groups, or in narrow strips. Seed trees do not provide enough shade to have an effect on regeneration. Seed trees are often light‑seeded, sun‑loving species whose seed is dispersed by the wind. Species that are more vulnerable to windthrow or wind breakage are not used as seed trees.

Figure 12. Red Pine Seed Tree Harvest

Shelterwood is the most complicated of the even‑aged systems and is an extension of the seed tree method. This method regenerates a new stand under the cover of a partial canopy called a shelterwood or overwood (Figure 13). The idea behind a shelterwood is that most tree species regenerate better in light to moderate shade, which provides a cooler, more moist environment, and the canopy of the overwood protects young seedlings from frost. This system is particularly useful for heavy‑seeded species (like oaks) or on harsh, droughty sites where regeneration following clearcutting can be problematic, but it can be successfully applied to almost any forest type. The shelterwood method involves two or more timber harvests: the first removes one-third to two-thirds of the mature trees, then when a young stand has regenerated and is well established the overwood is removed in another harvest. Sometimes part or all of the overwood is retained to create a more complex, two-aged stand structure and to grow really big trees. The new even-aged stand produced by this method can originate from seedlings, sprouts, or advance regeneration already established before the first harvest is done, depending on the species present and the ecology of the stand.

Figure 13. Oak Shelterwood

Uneven-Aged Systems

The uneven‑aged system uses the selection method of harvesting, which favors tree species that thrive in moderate to moderately-heavy shade. It is the most complex system and should be implemented by a professional forester. There are two basic variations. Single tree selection removes scattered individual trees or small groups of two or three trees, creating small gaps in the overstory canopy that favor regeneration of shade tolerant tree species (Figure 14). Group selection, on the other hand, creates larger gaps by harvesting all trees in a one-quarter to one-half acre area, which can allow shade mid-tolerant species like yellow birch, basswood, or white pine to become established. Natural regeneration in the gaps may already be present as advance seedling regeneration or can occur from fresh seed fall. In northern hardwood management, however, advance regeneration in the form of saplings and small poles should be cut because their poor growth potential and common deformities.

The uneven‑aged system uses the selection method of harvesting, which favors tree species that thrive in moderate to moderately-heavy shade. It is the most complex system and should be implemented by a professional forester. There are two basic variations. Single tree selection removes scattered individual trees or small groups of two or three trees, creating small gaps in the overstory canopy that favor regeneration of shade tolerant tree species (Figure 14). Group selection, on the other hand, creates larger gaps by harvesting all trees in a one-quarter to one-half acre area, which can allow shade mid-tolerant species like yellow birch, basswood, or white pine to become established. Natural regeneration in the gaps may already be present as advance seedling regeneration or can occur from fresh seed fall. In northern hardwood management, however, advance regeneration in the form of saplings and small poles should be cut because their poor growth potential and common deformities.

Figure 14. Canopy Gap and Regeneration

The successful application of this method depends on the condition and composition of the stand. It works best if a stand has at least three age or size (trunk diameter) classes or, better still, contains trees of all age classes, from seedlings to mature sawtimber. But the key to uneven-aged management is what is left behind in the residual stand after harvest (Figure 15). Trees to be cut should be individually selected from throughout all merchantable size classes so as to maintain or enhance the uneven-aged structure. It is also important not to cut too heavily in the largest diameter classes at any one time. If these principles are carefully followed, harvests can occur within the stand at regular time intervals of 10 to 15 years, called cutting cycles. The beauty of this method is that high-quality saw and veneer logs can be periodically harvested and generate income, yet the forest is retained. The selection system is the preferred management method for high quality northern hardwoods, where sugar maple is the major species, but it also works well in spruce-fir stands.

Figure 15. Post Harvest Northern Hardwoods

Selection of individual trees in a stand for retention or harvest is based on the species, quality, biodiversity concerns, wildlife habitat or mast production, and diameter class distribution. Selection system harvesting should concentrate on age classes or tree diameter ranges that are too dense for optimum growth and on trees that will not be in good condition at the end of the cutting cycle in 10‑15 years. Trees marked for harvest should, by their removal, allow better quality, more vigorous trees to grow and use their growing space. The goal is to leave a distribution or mix of tree sizes that maintains the stand in an uneven‑aged condition. Usually adequate regeneration occurs under this system, but spot scarification (exposing mineral soil) or planting can be used to increase species diversity or increase the regeneration of commercially valuable species.

The uneven-aged system works best in stands that already have many or at least three age or diameter classes. In many cases, stands of tree species that can be managed by the uneven-aged system were converted to an even‑aged structure through past cutting, fires, grazing, or other disturbances. Such stands can be managed using one of the even-aged systems. However, development of a diverse, uneven-aged structure can be fostered through careful thinning favoring potential crop and wildlife trees to increase diameter growth rates and development of advance regeneration, although this will still take many decades.

The uneven-aged system works best in stands that already have many or at least three age or diameter classes. In many cases, stands of tree species that can be managed by the uneven-aged system were converted to an even‑aged structure through past cutting, fires, grazing, or other disturbances. Such stands can be managed using one of the even-aged systems. However, development of a diverse, uneven-aged structure can be fostered through careful thinning favoring potential crop and wildlife trees to increase diameter growth rates and development of advance regeneration, although this will still take many decades.

Intermediate Treatments

Several tending treatments (operations carried out during the life of a stand but before final timber harvest) may be prescribed in even‑aged silvicultural systems to accomplish certain objectives. In young stands, thinning of dense regeneration and release of desired species from unwanted plant competition are applied to give the best trees more growing space and reduce the time needed to grow crop trees to a desired size. However, these treatments are a cost to the forest owner and are not always performed, despite their silvicultural benefit and the greater value they give to the final crop.

On the other hand, commercial thinning (the removal and sale of merchantable trees) is beneficial in all respects, usually associated with uneven-aged silvicultural systems. In Michigan commercial thinning should be performed whenever stands of intermediate-age are too dense and enough marketable trees can be cut to make the operation profitable. Thinning to proper densities by removing poorer quality tree stems and non‑commercial timber species frees the best trees from competition and allows them to grow faster in diameter. Thinning can be performed in any forest type that grows in Michigan, although it is seldom done in aspen or jack pine stands.

Pruning is the removal of living and dead limbs from the main stem of potential high-value crop trees. A tree properly pruned by cutting branches flush with the stem will produce knot-free wood once the wound heals over. Pruning also produces a more visually pleasing forest, for some people, and improves safety and access. Pruning is a good investment when knot‑free logs bring a premium price; e.g., with white pine, red oak, black cherry, or black walnut.

Prescribed fire is a useful silvicultural tool that simulates a natural ecological process. When fire is used as a tending operation in established, intermediate-aged or mature stands, it can reduce accumulation of fuels to lessen the chance of a destructive wildfire, improve wildlife habitat, discourage unwanted shrub or tree species, increase plant and animal biodiversity, reduce certain insects and diseases, and stimulate regeneration of favored trees. In Michigan, this type of prescribed fire is used in management of red pine stands or in oak and pine-oak savannas. Prescribed fire can also be used following a harvest of mature timber - principally clearcutting - to consume heavy accumulations of slash (residue following a timber sale) and prepare the site for natural seeding or planting.

Several tending treatments (operations carried out during the life of a stand but before final timber harvest) may be prescribed in even‑aged silvicultural systems to accomplish certain objectives. In young stands, thinning of dense regeneration and release of desired species from unwanted plant competition are applied to give the best trees more growing space and reduce the time needed to grow crop trees to a desired size. However, these treatments are a cost to the forest owner and are not always performed, despite their silvicultural benefit and the greater value they give to the final crop.

On the other hand, commercial thinning (the removal and sale of merchantable trees) is beneficial in all respects, usually associated with uneven-aged silvicultural systems. In Michigan commercial thinning should be performed whenever stands of intermediate-age are too dense and enough marketable trees can be cut to make the operation profitable. Thinning to proper densities by removing poorer quality tree stems and non‑commercial timber species frees the best trees from competition and allows them to grow faster in diameter. Thinning can be performed in any forest type that grows in Michigan, although it is seldom done in aspen or jack pine stands.

Pruning is the removal of living and dead limbs from the main stem of potential high-value crop trees. A tree properly pruned by cutting branches flush with the stem will produce knot-free wood once the wound heals over. Pruning also produces a more visually pleasing forest, for some people, and improves safety and access. Pruning is a good investment when knot‑free logs bring a premium price; e.g., with white pine, red oak, black cherry, or black walnut.

Prescribed fire is a useful silvicultural tool that simulates a natural ecological process. When fire is used as a tending operation in established, intermediate-aged or mature stands, it can reduce accumulation of fuels to lessen the chance of a destructive wildfire, improve wildlife habitat, discourage unwanted shrub or tree species, increase plant and animal biodiversity, reduce certain insects and diseases, and stimulate regeneration of favored trees. In Michigan, this type of prescribed fire is used in management of red pine stands or in oak and pine-oak savannas. Prescribed fire can also be used following a harvest of mature timber - principally clearcutting - to consume heavy accumulations of slash (residue following a timber sale) and prepare the site for natural seeding or planting.

Prescribed fire in red pine (left) and control area (not burned) in same stand

Special Management Considerations/ Protection

Forest Protection

Overall, Michigan's forests are healthy and productive. However, forests experience periods of stress and decline. Stress is caused by factors such as fire, drought, storms, late spring frosts, diseases, insects, and the advanced age of some especially shade intolerant forest types. These forests are most commonly even-aged with trees reaching maturity about the same time. Shade intolerant trees like aspen, northern pin oak, balsam fir, and jack pine do not live as long as shade tolerant trees and are more easily stressed once they reach maturity. Such trees most often mature around 50-70 years of age. Site conditions such as soil texture and moisture availability affect tree vigor and the tree’s response to biotic limiting factors (e.g. periodic defoliation). Declines, mortality, and/or fire hazard are an integral part of the ecology of Michigan's shade intolerant, forest types. Declines caused by periodic stresses, especially periods of drought, play a significant role in shaping Michigan's forests. Recognizing, understanding, and working with these, and other limiting natural processes and events, is an integral part of forest resource management.

Wildfire is a major concern in a forested landscape. Spring and fall are usually the periods of highest hazard due to the cured leaves, grass, and other vegetation that have accumulated from the previous growing season. Summer droughts can also be a time when serious wildfires may threaten the forest resource and interspersed homes. Increased numbers of people living in wildlands, along with diverse and increasing recreational use in the forest, have increased the risk of wildfire. Things to consider that could reduce the hazard of wildfire are limiting access to the area, establishing fuel breaks, reducing fuel (such as logging slash), and making users aware of fire danger.

The use of prescribed burning as a silvicultural treatment is a valuable tool in the management and regeneration of several tree species, particularly jack and red pine. Wildlife habitat, endangered species, and rare ecosystems may also be enhanced by the use of prescribed burning. There are definite hazards to prescribed burning. Prevention of escape requires special planning and preparation by experienced personnel.

More homes and housing developments in forested areas have added a new dimension to fire protection and the use of fire as a management tool. The people associated with this development bring with them the increased risk of wildfire ignitions. In addition, their structures now require additional suppression forces once a wildfire starts. Homeowners can reduce the risk of wildfire through the use of FIREWISE landscaping techniques. Information on the Firewise program is available on the Internet or from Michigan State University (MSU) Extension. Communities may want to consider developing Community Wildfire Protection Plans to reduce local risks. This is a collaborative process to reduce the risk of fire on neighboring public and private land. Contact the adjacent state or Federal land managing agency, which in Michigan could be the Bureau of Indian Affairs, USDA Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, USDA Forest Service, or the Michigan DNR for additional information.

Forest Health

Tree health and forest health are different things. A healthy tree is vigorous and disease free but not all trees in a forest should be healthy to have a healthy forest. A healthy forest supports many different life forms, some of which require components of dead, dying, and decaying trees.

Definitions of forest health closely reflect the values and beliefs of the observer. To one person, a vigorously growing forest producing a renewable timber resource is ideal. To another, the presence of specific habitats for wildlife species is paramount. Yet, another person would say that "letting nature take its course" is the ultimate in forest health.

A forest resource manager must balance resource demands based on a wide array of forest values. This requires an understanding and appreciation of all values, ability to compromise, a comprehensive inventory of the forest resource, and knowledge of limiting factors. A limiting factor is defined as a biotic or abiotic agent that has a negative influence on forest health and vigor of trees. Among the many limiting factors that affect the diversity, productivity, and vitality of Michigan’s forests are native and non-native insects and diseases, invasive plant species, and deer browsing; as well as abiotic stressors such as prolonged drought and poor soils. There are complex interactions within and between both biotic and abiotic limiting factors.

The most common biotic limiting factors are native insects and diseases which are components of natural ecological processes that periodically kill weakened trees. However, due to an expanding global economy, there is an ever-present threat of introducing new invasive plants, diseases, insects, and other animals. Non-native species have not evolved with and are not integral parts of native ecosystems. Consequently, many have no native biological controls to keep their populations in-check within the ecosystems that they invade. Non-native pests can cause new, and sometimes devastating, effects that disrupt natural ecological functions and processes and have major ecological consequences on the composition and health of native forest communities. Well known examples of invasive species include Dutch elm disease and chestnut blight which greatly reduced the number of American elm and American chestnut trees, respectively. More recently introduced invasive species include the emerald ash borer, beech bark disease, oak wilt, and the hemlock woolly adelgid.

Once an exotic agent like the emerald ash borer or oak wilt begins killing trees, they can be moved to new, sometimes very distant areas in firewood, nursery stock, or other wood products produced from infested trees. The responsible use and movement of firewood is currently the focus of public education and outreach. State and federal regulations are one way to reduce the introduction and spread of exotic pests in our forests.

Forest health information is available from forest resource managers and forest health specialists with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources & Environment and MSU Extension.

Overall, Michigan's forests are healthy and productive. However, forests experience periods of stress and decline. Stress is caused by factors such as fire, drought, storms, late spring frosts, diseases, insects, and the advanced age of some especially shade intolerant forest types. These forests are most commonly even-aged with trees reaching maturity about the same time. Shade intolerant trees like aspen, northern pin oak, balsam fir, and jack pine do not live as long as shade tolerant trees and are more easily stressed once they reach maturity. Such trees most often mature around 50-70 years of age. Site conditions such as soil texture and moisture availability affect tree vigor and the tree’s response to biotic limiting factors (e.g. periodic defoliation). Declines, mortality, and/or fire hazard are an integral part of the ecology of Michigan's shade intolerant, forest types. Declines caused by periodic stresses, especially periods of drought, play a significant role in shaping Michigan's forests. Recognizing, understanding, and working with these, and other limiting natural processes and events, is an integral part of forest resource management.

Wildfire is a major concern in a forested landscape. Spring and fall are usually the periods of highest hazard due to the cured leaves, grass, and other vegetation that have accumulated from the previous growing season. Summer droughts can also be a time when serious wildfires may threaten the forest resource and interspersed homes. Increased numbers of people living in wildlands, along with diverse and increasing recreational use in the forest, have increased the risk of wildfire. Things to consider that could reduce the hazard of wildfire are limiting access to the area, establishing fuel breaks, reducing fuel (such as logging slash), and making users aware of fire danger.

The use of prescribed burning as a silvicultural treatment is a valuable tool in the management and regeneration of several tree species, particularly jack and red pine. Wildlife habitat, endangered species, and rare ecosystems may also be enhanced by the use of prescribed burning. There are definite hazards to prescribed burning. Prevention of escape requires special planning and preparation by experienced personnel.

More homes and housing developments in forested areas have added a new dimension to fire protection and the use of fire as a management tool. The people associated with this development bring with them the increased risk of wildfire ignitions. In addition, their structures now require additional suppression forces once a wildfire starts. Homeowners can reduce the risk of wildfire through the use of FIREWISE landscaping techniques. Information on the Firewise program is available on the Internet or from Michigan State University (MSU) Extension. Communities may want to consider developing Community Wildfire Protection Plans to reduce local risks. This is a collaborative process to reduce the risk of fire on neighboring public and private land. Contact the adjacent state or Federal land managing agency, which in Michigan could be the Bureau of Indian Affairs, USDA Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service, USDA Forest Service, or the Michigan DNR for additional information.

Forest Health

Tree health and forest health are different things. A healthy tree is vigorous and disease free but not all trees in a forest should be healthy to have a healthy forest. A healthy forest supports many different life forms, some of which require components of dead, dying, and decaying trees.

Definitions of forest health closely reflect the values and beliefs of the observer. To one person, a vigorously growing forest producing a renewable timber resource is ideal. To another, the presence of specific habitats for wildlife species is paramount. Yet, another person would say that "letting nature take its course" is the ultimate in forest health.

A forest resource manager must balance resource demands based on a wide array of forest values. This requires an understanding and appreciation of all values, ability to compromise, a comprehensive inventory of the forest resource, and knowledge of limiting factors. A limiting factor is defined as a biotic or abiotic agent that has a negative influence on forest health and vigor of trees. Among the many limiting factors that affect the diversity, productivity, and vitality of Michigan’s forests are native and non-native insects and diseases, invasive plant species, and deer browsing; as well as abiotic stressors such as prolonged drought and poor soils. There are complex interactions within and between both biotic and abiotic limiting factors.

The most common biotic limiting factors are native insects and diseases which are components of natural ecological processes that periodically kill weakened trees. However, due to an expanding global economy, there is an ever-present threat of introducing new invasive plants, diseases, insects, and other animals. Non-native species have not evolved with and are not integral parts of native ecosystems. Consequently, many have no native biological controls to keep their populations in-check within the ecosystems that they invade. Non-native pests can cause new, and sometimes devastating, effects that disrupt natural ecological functions and processes and have major ecological consequences on the composition and health of native forest communities. Well known examples of invasive species include Dutch elm disease and chestnut blight which greatly reduced the number of American elm and American chestnut trees, respectively. More recently introduced invasive species include the emerald ash borer, beech bark disease, oak wilt, and the hemlock woolly adelgid.

Once an exotic agent like the emerald ash borer or oak wilt begins killing trees, they can be moved to new, sometimes very distant areas in firewood, nursery stock, or other wood products produced from infested trees. The responsible use and movement of firewood is currently the focus of public education and outreach. State and federal regulations are one way to reduce the introduction and spread of exotic pests in our forests.

Forest health information is available from forest resource managers and forest health specialists with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources & Environment and MSU Extension.

SOME RULES OF THUMB TO REMEMBER WHEN PLANTING TREES, TREATING TREES, OR SELECTING TREES TO LEAVE ON YOUR PROPERTY:

- Limiting factors which affect the growth and survival of selected tree species include soil, weather extremes, insects, diseases, and animal browsing.

- Soil requirements: consider soil texture, soil moisture, and fertility. Obtain a soil analysis.

- Site requirements: consider shade tolerance, wind tolerance, salt tolerance if along a salted road (most conifers are very susceptible to salt injury).

- How successful has this tree species been in neighboring areas on similar sites?

- Before deciding to treat an insect or disease problem, evaluate whether treatment is really needed for the health of the forest and if treatment alternatives are cost effective. Biological pesticides can be used if they are available, economic, and effective.

- Healthy and vigorous trees can usually withstand some periods of short‑term stress. Before deciding to remove trees due to forest health concerns, consult a forest resource professional.

Scenic and Recreation Values

Maintaining or improving the scenic quality of the forest is often an important objective for private forest owners, particularly near roads. A variety of scenic management objectives may be accommodated by modifying activities prescribed in special areas within the overall ownership. Special recreation management objectives may also be incorporated with scenic management efforts in forest management plans.

Although private forest management programs are rarely intended to provide for the full range of recreational uses that are present in a public forest, private forest owners often wish to incorporate hunting and hiking opportunities and, occasionally, camping or picnicking. Forest owners who wish to make special efforts to promote scenic or recreational objectives should consider the following suggestions in consultation with a professional forester.

Special Natural and Cultural Resources

Forests are more than just places where trees grow; they are places with many characteristics. Sometimes they are places where people live now. Sometimes they are places where people lived 100 or 1,000 or 10,000 years ago. Some forests are places with unusual geology or soils and they are places where rare plant communities or rare animals may live. Forest owners whose property contains special natural and cultural resources may have a legal responsibility to protect and preserve them.

Archaeological sites contain physical remains of almost 15,000 years of human occupation in the state. Written records cover only about two percent of our history. The rest must be gleaned from oral history and physical traces left by Michigan's earlier inhabitants. Cultural resources provide us with a link to understanding our own past, whether they are historic sites of old logging camps and homesteads, or prehistoric sites which remind us that, for centuries, people have been choosing the same places to live, work, and play. These sites contain important, irreplaceable information and sometimes artifacts of prior human activity and cultures.

Michigan’s forests are also home to a wide variety of plants and animals, some of which are rare or threatened by human activities. For example, if a forest is home to the endangered smallmouth salamander, the threatened bald eagle, or one of the rare moonworts; a forest owner may want to take these habitat needs under consideration when developing a management plan. Rare plants and animals are often restricted to certain microhabitats: the salamander, a vernal pool; the eagle, a large white pine near a lake; the moonwort, a sandy dune area. The significance of a particular kind of community in providing a species niche should not be overlooked when developing management plans. This often involves looking beyond a single property or stand of trees to a wider landscape level. It involves considering the actions of many forest owners, providing wildlife corridors, migratory stopovers, various sizes of forest patches, and the impact of invasive species on native communities. Forest owners and managers should be aware of cumulative impacts on rare species and communities. Individually, the loss may seem small, but over time and throughout its range, small losses of a species or community can add up to a significant impact.

Soil disturbing activities, such as the use of heavy equipment to cut trees and brush, build roads, and pull out stumps should be avoided in suspected sensitive areas until consultation is made with individuals trained in recognizing the special characteristics associated with special natural or archaeological sites. Forest owners and managers who may have special natural resources are encouraged to contact the Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) to discuss their resources and management options. The mission of the MNFI is to deliver the highest quality information that contributes to the conservation of biodiversity, especially rare and declining plants and animals, and the diversity of ecosystems native to Michigan. Forest owners with potential archeological resources may also wish to contact the Office of the State Archaeologist (OSA). The OSA records, investigates, interprets, and protects Michigan's archaeological sites.

Legal responsibility for special natural resources can be found in both the Federal Endangered Species Act and the Michigan Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act (Public Act 451).

Maintaining or improving the scenic quality of the forest is often an important objective for private forest owners, particularly near roads. A variety of scenic management objectives may be accommodated by modifying activities prescribed in special areas within the overall ownership. Special recreation management objectives may also be incorporated with scenic management efforts in forest management plans.

Although private forest management programs are rarely intended to provide for the full range of recreational uses that are present in a public forest, private forest owners often wish to incorporate hunting and hiking opportunities and, occasionally, camping or picnicking. Forest owners who wish to make special efforts to promote scenic or recreational objectives should consider the following suggestions in consultation with a professional forester.

- The design and layout of access roads should be considered in conjunction with recreational and scenic objectives. Access roads may be designed to provide for permanent recreational driving access, for future use as foot trails or ORV trails, or they may be designed to be abandoned and re-vegetated after the cutting activity is completed.

- The modification of the normal harvest prescription may include eliminating clearcuts near roads or modifying the edges of clearcuts to blend with the landscape. Thinning may be modified to emphasize big tree character or clearcuts may be introduced where they would not normally be used in order to create scenic vistas.

- Avoid or modify cutting activity where unique natural features such as rocky bluffs, sand dunes, or groups of unusual trees are located.

Special Natural and Cultural Resources

Forests are more than just places where trees grow; they are places with many characteristics. Sometimes they are places where people live now. Sometimes they are places where people lived 100 or 1,000 or 10,000 years ago. Some forests are places with unusual geology or soils and they are places where rare plant communities or rare animals may live. Forest owners whose property contains special natural and cultural resources may have a legal responsibility to protect and preserve them.

Archaeological sites contain physical remains of almost 15,000 years of human occupation in the state. Written records cover only about two percent of our history. The rest must be gleaned from oral history and physical traces left by Michigan's earlier inhabitants. Cultural resources provide us with a link to understanding our own past, whether they are historic sites of old logging camps and homesteads, or prehistoric sites which remind us that, for centuries, people have been choosing the same places to live, work, and play. These sites contain important, irreplaceable information and sometimes artifacts of prior human activity and cultures.